Key work is focussed on developing ideas around better sharing of evidence-based use of digital technology. This strand has focussed on the need for teachers to develop and exchange clear, evidence based strategies for using digital technology and improving their skills to use it effectively.

In particular, there is a clear need for better use of evidence. The challenge is to identify how digital technology should fit into the wider picture of increasing professionalisation of the teaching profession. How might something relating to digital technology fit with the work (for example) to develop a college of teachers or existing initiatives to share ideas and information.

We concluded that the use of digital technology in education is not optional. Competence with digital technology to find information, create and share knowledge is an essential contemporary skill set. It belongs at the heart of education and learners should receive recognition for their level of mastery.

Education leaders, heads of institutions, are in a difficult position, juggling impossible demands with little funding, and are too hand-to-mouth to invest properly in innovation. They need to be aware that digital technology can help them solve their problems, if they could have time and support to think it through, and find a way to invest. If at all levels of leadership there were recognition of the need to invest in both adoption of innovation and development of innovative new approaches, with the expectation of rewards in the longer term, not necessarily within the budget year, then they might be enabled to move forward.

A systemic analysis

Education is a complex system of national, local and institutional stakeholders, public and private institutions and forces, and a broad range of professionals. It takes responsibility for conducting every student through the formal education that should enable them to attain their learning potential, for the benefit of both individuals and society. The complexity of this system means that developing and embedding any radical change requires a clear understanding of how it operates, because its complexity makes it highly resistant to change.

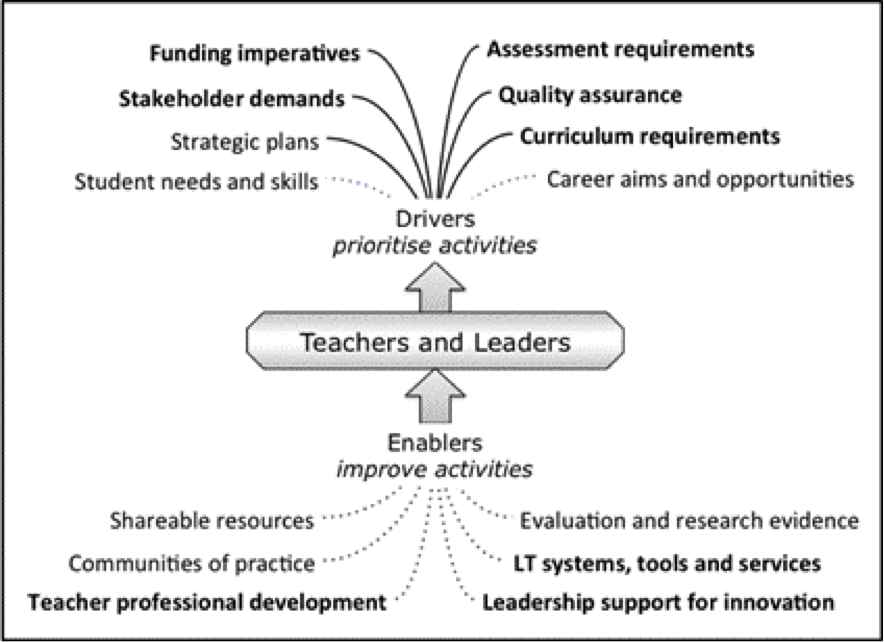

To gain some traction on this complexity, it is useful to think in terms of how teachers and leaders prioritise their work and practice, because the comparative strength of all the competing influences determines the success of any one initiative for change and innovation. The principal ‘drivers’ are the elements of the education system that determine how the teachers and leaders are likely to prioritise activities. Unfortunately, innovations in ICT are not demanded by most of the drivers. These are, roughly in order of decreasing power (though not necessarily importance):

- funding imperatives,

- assessment requirements,

- stakeholder demands,

- quality assurance,

- strategic plans,

- curriculum requirements,

- students’ individual needs and skills,

- teachers’ career opportunities (Laurillard, 2013).

If, for example, there were a funding imperative to adopt innovations or develop and share new practices in teaching, then this would become a priority for teachers.

The drivers in a system define the influences a professional cannot ignore, so they will act to prioritise activities that respond to them. But they are not sufficient for effective action without the ‘enablers’, i.e. the mechanisms the professional cannot do without if they are to respond effectively to the drivers.

If we consider the balance between drivers and enablers for the case of innovation in learning technology, the relevant enablers are those that best support teachers and leaders in the change process. These are:

- leadership support for innovation,

- teacher professional development,

- learning technology tools, systems and services,

- communities of practice,

- shareable resources,

- evaluation and research evidence.

Figure 3 illustrates the relative strengths and weaknesses of these influences on the actions of teachers and leaders.

Figure 3: the drivers of professional activity in the education system balanced against the enablers for innovation in learning technology (bold indicates the more powerful ones)

The question is: are the drivers sufficient to prioritise innovation in learning technology, and are the enablers in place to support it?

None of the principal drivers demand that teachers prioritise adoption or development of innovations in teaching, whether with digital technology or otherwise. So a powerful way for the Minister to promote change, therefore, would be:

to require each agency responsible for these drivers to report on how it would change its approach to ensure that teachers prioritise innovation with learning technology.

Similarly, the enabling mechanisms remain starved of funding, and with little or no strategic priority for developing and sustaining them. They will continue, and given the absence of any clear drivers for learning technology innovation they will remain its main source in the future, but being so localised, they cannot be a force for system change. This systemic analysis suggests two systemic actions: to update the drivers, and develop the enablers. The first is in the hands of the agencies and leaders responsible for the drivers, and the second could be developed as a holistic system working in support of teachers and leaders who wish to innovate.

The alternative is that the system will continue to rely on piecemeal local innovations in teaching and learning that have no large systemic effect. At institutional level and at national level, education leaders must consider their own responsibility for innovation.

Updating educational drivers and enablers to keep pace with the digital world could be sustainable and progressive over the long term, and would make innovation affordable as a natural part of how institutions operate.

Learning technology and the teacher

Teachers who move to online teaching will be aware of a significant, but only initial, increase in their workload, if they are setting out to make optimal use of the technology. It involves several new kinds of teaching activity:

- Planning for how students will learn in the mix of the physical, digital and social learning spaces designed for them

- Curating and adapting existing digital content resources (for reading, listening, watching)

- Selecting the online tools and resources for all types of active learning (for inquiry, discussion, practice, collaboration, production)

- Designing and developing the independent learning activities for all these types of learning

- Developing the personalised and adaptive teaching that improves on conventional methods

- Scheduling for flexibility in blended learning options

- Managing the tutor role in online discussion groups

- Using technology to improve the efficiency of qualitative feedback

- Designing, monitoring, interpreting and using the new and more sophisticated learning analytics, which can give the teacher a clearer representation of where the teaching needs to improve.

There are several resource repositories but very few tools to support teaching design. Too often, teachers in all sectors are given inadequate opportunity to develop these skills. As a professional community teachers could be building our practical knowledge of how to optimise teaching with technology. This could also be part of ‘a holistic system working in support of teachers and leaders who wish to innovate’.

Learning technology and the student

Teachers are increasingly aware of the prodigious digital skills of some of their students, who barely need their help in working with technology. The problem is that these students do not necessarily understand how to learn with technology, and for this they do need help. There is also the problem that there are still some 800,000 students with no home access to a digital learning environment, and many more who are not digitally skilled. But teachers are finding ways of managing both ends of this spectrum very effectively, through the ‘digital leaders’ programme. Digital Leaders are students chosen for their high level of interest and digital skills, and their ability to support class teachers in their use of learning technologies. This has become common practice in primary and secondary schools in the UK.

These students sometimes help the younger classes, or are responsible for the distribution, collection, charging and storage of devices, or support teachers in lessons that use technology. The programme creates a broad range of learning benefits:

- By supporting learning technology activities they begin to realise they have to be able to give instructions fluently and be flexible in social negotiation.

- They practice their ability to provide instructions and explanations for a variety of student colleagues.

- They are scaffolding the learning process for other less able students.

- By explaining to other pupils, Digital Leaders can model and remodel the knowledge they have acquired and refine it by the process of having to explain and teach others.

- They reflect regularly on their practice and implementation in training sessions with each other and with the teacher.

- Self-confidence and independent working is increasing among the Digital Leaders, because of this use of their skills, even though some are below average in other core subjects.

- They enable teachers to use mobile devices more often in their lessons since they do not have to ensure that they are charged, or collected, they merely have to book them out.

The teacher is then able to focus on the general classroom organisation and overview of the students’ work, orchestrating and intervening where necessary to facilitate learning, to tutor the basic knowledge, to ask pertinent questions, open or closed where appropriate, and spend more time on assessment for learning.

Harnessing students’ skills and imagination in the use of learning technologies, managed carefully across the curriculum, will bring real advantages to every school if the programme is now adopted universally.

The role of government and official bodies

Every organisation must invest in order to adapt to its changing environment. We cannot ignore the imperative to invest in teaching, especially when learning technologies present such impressive opportunities for improving the way we do it.

At every level of the education system its leaders must find ways to invest in the innovation that will create effective and sustainable models for conducting education, and achieve our ambitions for higher attainment, and students’ continuing access to and commitment to learning. In an adverse financial climate this is hard, but if we can harness the professional interest, capability and digital skills of all teachers to contribute to and learn from collective innovations, then the profession as a whole, and students in particular, will benefit. Some will be innovation leaders, others will be adopters of others’ innovations, but it is feasible for every teacher to be a specialist technology innovator with respect to some topic, or skill, or learning approach. The challenge is to bring them together in a coordinated long-term programme of collective innovation.

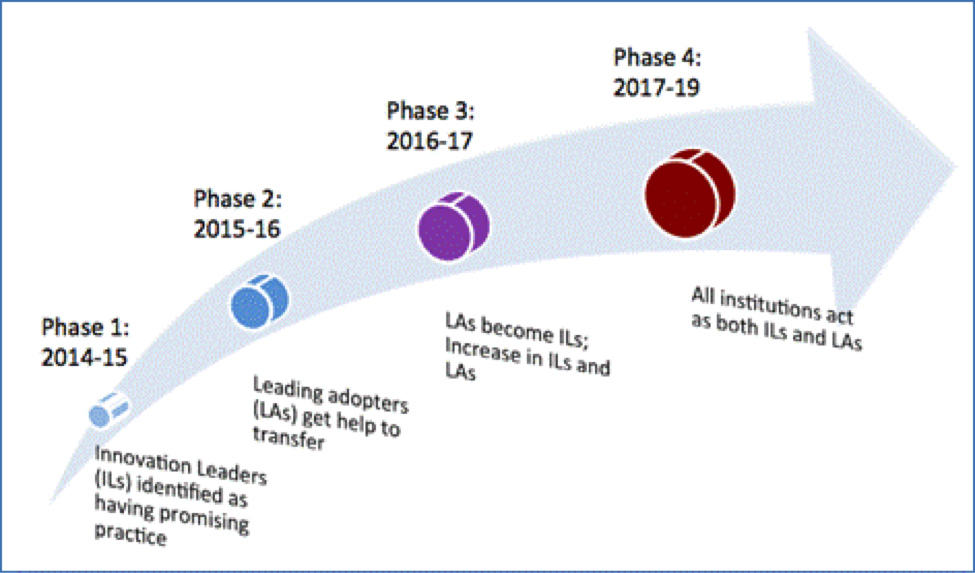

Figure 4 imagines a rolling programme of innovation and adoption, building towards a system in which every school, and every teacher, is both specialist innovator and generalist adopter, enabling education to become a learning system that can adapt to what will certainly be an ever-changing environment.

Teachers, Heads and schools need the signal from government and official bodies that it is important and valuable to invest their time and energy in learning technology innovations. At present the drivers they are responsible for prioritise the conventional, and have not adapted to prioritising the new and the digital. The ideas and innovations will develop bottom-up, but the recognition, incentives and rewards can only be top-down.